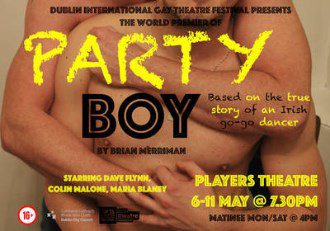

Party Boy – Gay Theatre Festival – Review

Patrick, a young gay Irish man, is the star of Brian Merriman’s play “Party Boy”. Presented in the small, intimate space of the Players Theatre in Trinity College, the play takes the audience on a riveting journey through Patrick’s young life: and it’s all based on a true story.

The boy meets the scary spectre of homophobia from a very young age, spending the later years of his childhood exploring his sexuality in his first same-sex encounters. But soon Patrick’s heritage as a Catholic, gay, Irish boy comes knocking, and he finds himself presenting himself as straight. Episodes of traumatic bullying experiences in a Catholic school and his constant being harassed as “queer” force him into the closet.

Through it all, and able to see through the darkest of closets, stands Patrick’s mother. A no-nonsense strong woman, always available to listen to her young son’s needs, Maria Blaney brings on stage the Irish mammy we all wish we had.

Together with Colin Malone, the two actors provide great, entertaining support to Dave Flynn, taking on many different characters created with a simple prop or costume change, providing snippets into the rolling film of young Patrick’s life.

From Ireland to Australia and then back again: the sex is getting wilder and more available, his body is getting him a long way and he is riding the wave of the good life. But behind the flash and the –very in-your-face – live sex shows, a rot is starting to spread; drugs, alcohol and medicated sex. Gay men dying off like flies. Go-go boys dancing provocatively. Young Patrick’s life gives us all, especially for those who weren’t there to see it for themselves, an insight into what it meant to be gay in the early 2000s, and how important it is to be supported by your loved ones.

Patrick is one of the few that survived or avoided abusive relationships, AIDS, drug overdoses and falling into a desensitised and medicated life because of his life-buoy, his mother.

In an Ireland where homophobia still lurks on the streets, Patrick’s proud tale of his uninhibited life between sex, drugs and relentless loves is a cautionary tale (not to be taken too seriously!) for a young audience, a trip down memory lane for middle aged ones, and a great insight into what it means to be gay, to be sharing the life of the underground gay community and to instruct us all how it is, sometimes, good to just be a party boy.

An exuberant and chilling hurricane of a play

It’s all about the sex.

Except of course, it isn’t. Not really.

There is plenty of sex — don’t get me wrong. But Brian Merriman’s kaleidascopic 75-minute epic, “Party Boy,” is a more than just a peep show into the contemporary world of the gay male porn industry, with all of its glamour, heartache, and lethal drug scene.

It’s also a whirlwind journey through some of modern Ireland’s most complicated social issues, beginning with the historically repressive influence of the Catholic Church on, well, everybody, continuing on through the heady and tumultuous years of the Celtic Tiger, and venturing into Ireland’s vaguely uncertain future as the EU re-invents itself and the island struggles with related complexities arising from immigration, patchy economic stability, rapid social change, and escalating internationalism.

All of which sounds a whole lot more cerebral than “Party Boy” feels when you’re in the audience, completely immersed in the rapid-fire action and the glittering dialogue. Everything about this piece pulls you into it, from the first moment the young and beautiful protagonist, “Patrick,” arrives on stage as a winsome, winning pre-teen gay, to the final moments when he thrashes and flails against that most unrelenting of enemies of the club scene — the aging process. Along the way, we watch him reel from one lover to the next, from one social media “triumph” to another, and from one excruciatingly public sex act to even more graphic performances for even larger audiences. All the while convincing himself that this is what “success” looks like, feels like, in the newly liberated gay scene, despite the viciously oppressive nature of the porn industry and the spiraling mortality rates it provokes among its victims…who are also its biggest stars.

Actually, such is the artistry with which “Party Boy” is crafted that we don’t just watch Patrick as he soars towards his own destruction, so much as we actually join him on that gruesome but glossy trajectory. Every aspect of the dramatic arts is maximized to pull the viewer into Patrick’s world, as dangerously exotic as that world might be. A simple but effective set design and a soundtrack so perfect that, like a good football referee, it keeps the game going without calling overdue attention to itself, combine with creative blocking and almost acrobatic wardrobe changes that enable the two “supporting” players to portray a multitude of characters, some of which have a fleeting presence in Patrick’s life and others of whom are are the absolute bedrock without which it simply wouldn’t be possible. Casting is pitch-perfect, with a palpable rapport among the three players and deft directing encouraging award-worthy performances from each of them.

The principle bedrock presence is Patrick’s single-parent mother, played with artistry, compassion, and insight by Maria Blaney, who also “doubles” as the other female characters in the piece and, with great aplomb in one unforgettable scene, as a gay male stripper, which would surely qualify her for a “Good Sport Award” if the Festival had one. Like her two on-stage colleagues, Blaney repeatedly turns on a dime as she switches from one character and one time period to another, never missing a beat and managing to inhabit each of these various persona with equal ‘believability’ as they literally tumble down upon her.

Merriman is known for his commitment to writing parts for women that illustrate their pivotal role in Irish history and culture, even when that history and culture conspire to ‘invisiblise’ them, and “Party Boy” is no exception. But the on-stage role of “Patrick’s mother” is more than just the narrative glue that helps hold the play together in the same way that the real Patrick’s mother held his life. Blaney takes the opportunity presented by the figure of the relatively traditional Irish mother, who doesn’t understand her gay son but loves him with a desperate generosity, and runs with it. She runs far and fast, and brings the audience along with her to a new understanding of what “love” can look like.

By the time we’re halfway through the play, we’ve bought into her unconventional approach to keeping her son alive while others are falling all around him, despite what it costs her, personally, in social cachet and actual money. As “Gay Lib” caught hold and the drug use within club culture proliferated, there must have been thousands of mothers all over Ireland, faced with similar dilemmas and given no resources for dealing with them. Patrick’s mother emerges as the only real hero in this tale, with a quiet kind of valiance that achieves its goal without fanfare or joy.

Colin Malone turns in an equally stunning set of performances as an entire host of male characters populating Patrick’s life, a range of personae that includes his childhood play-mates, his lumpishly terrifying father, multiple lovers, and at least one good friend and potential life partner, whose devotion to the aging Patrick occasions the single most chilling line in the entire play. Malone is, quite literally, astonishing in his range and elasticity, moving from one persona to another with effortless ease and absolute authenticity. He is also quite a physical actor, adept at translating interior states into observable styling as well as impeccably accurate dramatic rendering, equally believable across a panapoly of ages, ethnicities, sexuality, and class. The directorial vision for this production of “Party Boy” requires huge athleticism from all of its cast members, but perhaps Malone most of all, since he must, literally, spin among stage persona as often as Blaney, but with more radical costume changes and often more theatrical phsyicality associated with them.

For instance, he plays a number of Patrick’s sex partners, some of whom are in it for the money more than for the pleasure and/or the glory of sleeping with Ireland’s most sought-after prince of gay go-go. This often requires him to take the lead in carefully choreographed sex scenes that cross classic porn rituals with kabuki-like staging, a physically taxing undertaking if ever there was one. Malone handles this, and more, with high style and convincing detail, keeping the show moving along its interstellar orbit at warp speed.

Dave Flynn’s rendition of the ‘party boy’ himself is, quite simply, electrifying. From the moment he walks onstage to the minute after the metaphoric curtain falls, he is a high-energy orb of pure visual delight. The man literally never stands still; even when he’s standing front and centre to the audience, pulling us into the next chapter of his life with another dense, rich monologue, he is bouncing slightly on the balls of his feet. “Patrick” is a man in motion just as much as his life is a hurricane of blurred faces, bad drugs, disposable friends and nameless yearning, in which only the sex itself stands out as memorable and momentarily real, until even that begins to falter.

Although, unlike his colleagues, Flynn inhabits only a single character throughout the course of the play, he still has to pivot in and out of radically different versions of that character, as Patrick grows from boy to man and then begins his odyssey deep into the dark life of commercial sex. He does this well and gracefully, never dropping a beat or missing a note as he whirls from one dizzying episode to another, always managing to bring us, the whip-lashed audience, along with him. It’s an almost impossible piece of stagecraft — and part of what makes this play a true stand-out in contemporary Irish theatre, as well as in gay drama, per se.

But Patrick’s story is not one great headlong scramble towards disaster. What really puts the stamp of ‘unforget-ability’ on Flynn’s performance is the reckless joy with which he imbues his existentially doomed lead character. Patrick certainly faces some somber moments, and some horrifying ones, too. He is not impervious to the ‘lethality’ of the world in which he lives, and wants to dominate. He has a sense of “at what price stardom?” but he is also a flighty kind of pragmatist in that he seizes the opportunities of the moment without much thought for their eventual, cumulative impact over the full course of his life. He can also be carelessly ruthless, with his own body as well as with other people’s hearts. But as Flynn plays him, Patrick is also an enormously likeable character, a boy who never really grows into a man, despite having never really been a child in the first place. There is a fierce joy in him, a reckless but compelling exuberance, which makes his descent into self-destruction all the more crushing.

In some ways, although it takes place a bit later on the gay history timeline, Patrick’s story epitomizes the intoxicating sense of freedom that flooded gay communities everywhere during the early 1980’s, before AIDS and after the first wave of (relative) social tolerance began working its way into mainstream societies. Although Patrick’s personal story is the extreme version of that phenomenon, Flynn still harvests that soaring sense of collective identity and the eruptive glee of finally having places to go where one’s sexual self need not be strangled into silence in order to preserve one’s basic social viability. There’s a lot of backstory to “Party Boy,” and more to the hedonism of club culture than immediately meets the eye. Flynn’s nimble and sympathetic performance makes no excuses for the ravages that culture could inflict, but it also illuminates the complexities of it in rich and socially crucial ways.

At the end of the day, “Party Boy” is a tour-de-force that captures life on the hard-core club circuit with almost ethnographic accuracy, right down to weaving “tricks of the trade” and specialized lingo into the fast-moving main narrative. It is also ambitious in scope, sweeping outwards from Dublin to illustrate the global network in which Ireland is only one small part. I will never walk through an international airport again without wondering who, among my fellow passengers — male and female — might leave the Arrivals Hall only to sink into the grimy glitz of the international sex trade, in which even its stars are, in the long run, the bottom rung of the porn industry’s cannabalistic food chain. Merriman and the cast and crew of “Party Boy” have succeeded in creating that unicorn of the dramatic arts…a play that entertains, engages, and educates the audience by turns and sometimes simultaneously, and that changes how those viewers will forever see the world outside of the theatre walls.

Read the full article by Kerric Harvey on our Facebook page.